The burn I got from touching the hot bending-iron in my father’s workshop

The burn I got from touching the hot bending-iron in my father’s workshop

at the age of four was my first contact with the art of guitar-making.

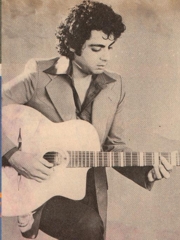

My mother, who went to help out in the workshop from time to time would take me with her. When I was little, the guitars seemed enormous and hand-calluses today have replaced the blisters of my childhood. When I was 13, I was given a Christmas present of …a classical guitar. “Here you are, this is just what you want. You start the guitar course on Saturday with M. Garcia the guitar teacher.

If one day you become a guitar-maker, you’ll thank me.”

I am still thanking you !

After year 11 at the lycée Jacques Decourt, I studied from age 16 to 20 in the college of Applied Arts, also helping at the workshop at 9 rue de Clignancourt, and in the end I was steeped in the pleasure of playing and making guitars, the two things being very closely linked for me. I tried my hand at all guitar styles, encouraged by the music I heard. Musical notes replaced lessons in class for me.

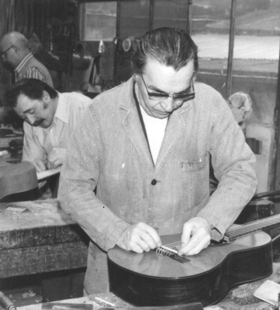

Every Thursday and Saturday from 1968 to 1972 I made guitar parts: sawing mahogany and rosewood to make the bodies, strengthening bars, struts for the harmony table or bottom, gluing the sides together. “Remember, this is half of your apprenticeship done”.

I was grateful for this moment of encouragement.

I helped with the finishing touches before varnishing and, little by little, started to put together classical guitar frames, guitars for beginners. “I’ll show you how we do this, and after you’ll find your own way”. I am grateful for this freedom given to me early in my career. Working with others has been, I know, an immense shared pleasure.

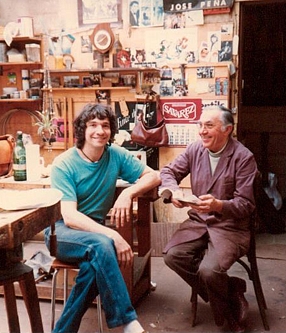

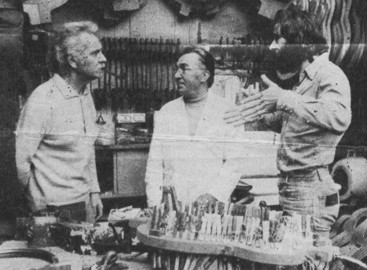

Three pairs of eyes watched me… The work was shared between my uncle Gino Papiri, Ugo Terraneo and my father Jacques Favino, who also trusted me with the repairs which I could do, on all and every make of guitar which the customers brought to us. I learned to find solutions to problems, because each repair is different, working out the structures and understanding the mechanisms. This was a good school. Ugo and Gino were always behind me, more so than my father. The boss’s son got away with nothing and I am grateful for it.

From time to time they sent me to deliver classical or jazz guitars to music shops; Vincent Génod, rue de Rome, was the last retailer we supplied. Japanese, Korean, and then Chinese imports have in a large part taken the place of artisan productions; this nevertheless played a role in making the guitar more accessible to a wider public: cheap, mass-produced guitars allowed beginners to start playing the instrument, which was always more expensive when bought from a local guitar-maker. If the player improves as much in his listening as in his playing technique he will want a better quality instrument, and will decide to buy himself his own guitar, specially designed for him by a specialist guitar maker (stringed-instrument maker).

Most of the classical guitars we were producing for study or concerts were destined for students from the music conservatory or studio musicians.

Teachers or concert artists were supplied by specialist classical guitar makers as our reputation as jazz guitar makers discouraged them.

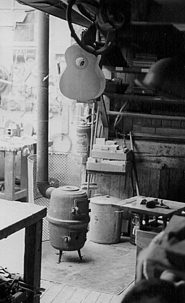

Le poêle I had, and still have, more than enough energy, so I had to learn to be patient. I would lose my temper when I got a piece of work wrong. “Pay attention to what you are doing!” adding a bit later: “Don’t worry; only people who don’t attempt a job will not make mistakes”.

Le poêle I had, and still have, more than enough energy, so I had to learn to be patient. I would lose my temper when I got a piece of work wrong. “Pay attention to what you are doing!” adding a bit later: “Don’t worry; only people who don’t attempt a job will not make mistakes”.

My father was able to make a bridge by one simple gesture, producing one wood shaving, whereas for a similar operation I needed ten gestures and as many wood shavings. I often suggested trying a new method of assembly for the guitar. “Do it! I also experimented and found ways to do things. You will find your own solutions”. At the end of 1973 I became part of the team; then the adventure really started.

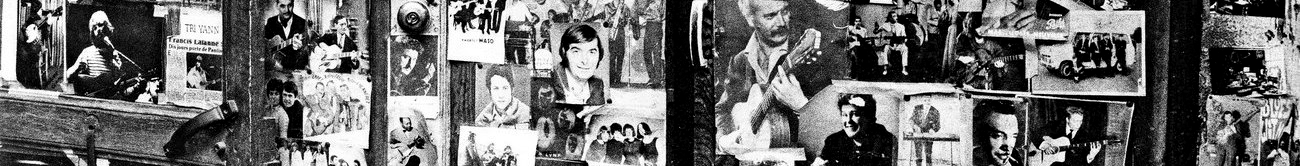

Friends and customers popped in and out, amateurs, beginners or professionals, all passionate about the guitar. They often came together for a jam session and to try out the new guitars. If they spoke different languages, they played with a look of complicity and without a word. We listened to guitar music while we worked. I listened to them chatting, asking their questions of my father, who, at the same time, watched their style of play, memorising their position, suggestions and remarks and noting each of their requirements in an order-book. “In fact it is the musicians who’ll teach you the job”.

I am grateful for this broad-minded attitude. This atmosphere familiarised me with the ways of the wood workers. We would speak about velvety, round, warm, clear, incisive, precise and distinct sounds; one can say that a guitar is seasoned, an expression which in fact can be used of nearly all crafted instruments. They mature, if they are played, that is, and improve like good wine! Maurice Ferret said to us one day: “Wow! Isn’t this one bold!” He was talking about a guitar. So many words only to speak of one thing: the sound.

We would speak about velvety, round, warm, clear, incisive, precise and distinct sounds; one can say that a guitar is seasoned, an expression which in fact can be used of nearly all crafted instruments. They mature, if they are played, that is, and improve like good wine! Maurice Ferret said to us one day: “Wow! Isn’t this one bold!” He was talking about a guitar. So many words only to speak of one thing: the sound.

To hear and to watch the guitarist, with his instrument in his arms, is basic to understanding what he wants; play the guitar, play on a guitar, play with a guitar are the many attitudes of the guitarist.

In winter, when we arrived at 8 o’clock, the temperature of the workshop was the same as outside. It took about two hours for the stove to start giving out some warmth and for the more arduous physical tasks to make us feel comfortable. Working under a glass roof is a blessing because of the light it lets in… From April to July, the sun turned us into tropical plants!

Pushing the front door open would produce a tinkle from the bell and the spiral staircase would take you to the workshop on the first floor. After hearing the bell, we often heard a series of swear words about “that damn steep staircase”. It meant that our visitor was Colette Magny. When she arrived at last, she would sing for us whatever she had just composed: she made the windows shake. Her voice was past its best, we remember it at its best. The tinkle of the bell can still be heard, too.

Accustomed from childhood to famous visitors, I wasn’t a bit shy. To me they were musicians and nothing more. And yet, the first time I saw Brassens turn up in the workshop, it was different. The man whose songs had provided a background for the whole of my generation was there, in the flesh, and smiling at me. After my “Hello, Monsieur Brassens, Sir”, he said, “You just call me George, like everyone else”. Like everyone else, except that he and my father always stood on ceremony with each other, increasing their mutual respect and shyness by their formality.

They only started calling each other ‘Georges’ and ‘Jacques’ shortly before being separated by death.

He would phone before coming to have one of his guitars seen to: “Tell me if this is inconvenient, but I would need to bring you a guitar. May I come?” This is what I call respect. My work is also my pleasure.

He would phone before coming to have one of his guitars seen to: “Tell me if this is inconvenient, but I would need to bring you a guitar. May I come?” This is what I call respect. My work is also my pleasure.

When Ricet Barrier brought me the 6-string folk guitar which my father had made for him in the sixties, I noticed how worn the varnish along the right-hand side of the top was, near the end of the fingerboard. “Please don’t interfere with that area”, he said. And, smiling, he told me why: “I play the strings with my thumb, and I let my fingers scrape the wood there, as an imitation of brushes on a drum. Now that I have worn the varnish off, the sound is right”. With time, the softer parts of the wood had gone, leaving ridges of harder grain, creating a miniature washboard. He demonstrated it for me with a malicious smile: fantastic!

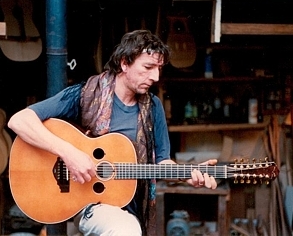

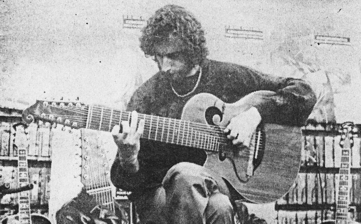

Nobody ever talks of guitarist-makers. Yet, among those who have widely communicated a love of the guitar, Django Reinhhardt and Georges Brassens must be mentioned. All those who caught the bug from either of these two will never recover from it. The 12-string guitar is not a 6-string guitar to which six extra strings have been added without a full overhaul of the design. It was an amateur musician, and a great lover of the 12-string, Jean-Pierre Lebarbenchon, who led me towards my greatest successes in this field. His technical skill justifies his being so exacting. My father made him his first one, in 1976, and I made the next six, between 1980 and 1989, all of the three-rosace jumbo type.

The 12-string guitar is not a 6-string guitar to which six extra strings have been added without a full overhaul of the design. It was an amateur musician, and a great lover of the 12-string, Jean-Pierre Lebarbenchon, who led me towards my greatest successes in this field. His technical skill justifies his being so exacting. My father made him his first one, in 1976, and I made the next six, between 1980 and 1989, all of the three-rosace jumbo type.

Each guitar has shown an improvement on the previous one: the pitch of each string (because he plays the strings separately) and the balance between stiffness and flexibility of play are only two of the main points. I am glad he was so demanding and nevertheless trusted me. As demanding, but with a different style, is Michel Gentils. He has made some marvellous recordings. He owns two three-rosace guitars with twelve strings, tuned sympathetically in one case.

It is when you find your pride challenged that you make progress…

When you play music, all the rest disappears. Dany Brillant, a very shy man, came to see me one day about a jazz guitar he wanted to purchase. When I suggested he try out a model I had on the premises, so that I could see what he wanted, his reserve then suddenly flew away. What a musician he is! And what swing he has! If he used a guitar on stage, he would reveal that he isn’t just a singer, but also a true musician.

There are many guitarists who show promise from their very beginnings. When we meet them in the workshop, when they strike their first notes, everyone will stop work, silence will fall and knowing looks will pass from one to other, to show they understand something great is happening.

Such moments make you feel happy to be making guitars.

In 1978, my uncle and my father retired and another uncle, Jean Maddonini, was hired until 1980 to replace them in the team. Ugo left in late 1983.

In 1978, my uncle and my father retired and another uncle, Jean Maddonini, was hired until 1980 to replace them in the team. Ugo left in late 1983.

The telephone introduces formality into our relationships. Matelo Ferré, who knew me before I could walk and would treat me as a kid in the workshop, would always use the polite “vous” form when speaking to me on the phone. Immediately on arrival he would try out any guitar that was lying around and utter the same invariable comment: “This little guitar has a fine sound, all right”. It must be said that when Matelo was playing it, any guitar would sound marvellous. Everyone admired his hands, his playing and his modesty.

During my first week on my own, I « was going nowhere » with my work, without understanding why. Then I realised that the workshop had been laid out for four people and I had to reorganise it to ergonomically suit one worker. I moved the workbenches around, found my favourite nook. Only my movements and the sound of my tools peopled this space. This went on for seven years.

Wanting to look after the constructions, repairs, settings, customer relations, management and of course answer the phone, I discovered that it was too much for one man, as they say.

The solution presented itself in 1990, when I moved to Castelbiague, in the Haute-Garonne. I discovered that the silence of natural spaces was really what I was looking for.

“You have no right to be going away !”

A few faithful customers were unhappy not to have me close at hand any more. The first four years were a bit hard, but, on balance, the incomparable quality of life cancels that old memory. I was able to organise my own space. I learned to slow down my movements at the workbench, to polish off the most minute details, and my work evolves in accordance with my ideas. Customers visit by appointment, and we take our time.

To dream and meditate gives you an open-mind where ideas can be developed: you just let them percolate through. That’s the real meaning of the word creation. In my opinion, we only receive what is already there.

After thinking hard about it, drawing plans and possibly making a model, I produce a new type of guitar: my aim is to turn what seemed heretical into something which will be accepted generally…

Il y avait dans l'atelier parisien, un grand miroir, dans le bureau qui servait à essayer nos instruments. In the office of the Paris workshop, there used to be a large mirror in front of which the musicians would try on the guitars, as you try on a garment. When your instrument is part of your myth, it takes courage to make a change. I have always found pleasure in making the same models of guitars, because, in fact, each guitar, being built specifically for a musician, is unique. But at the same time I need to express myself in my creations. Besides two flamenco-classical guitars for Yves Duteil, I also made, at his request, a third one with 12 nylon strings. Later he told me the tunes he composed on this instrument were different. I was delighted.

I am thankful to those “original” musicians with whom I can get out of the mould of traditional guitar-making. Our collaborative experiments enrich the design of all the other models, albeit in minute details. Inquisitive minds think alike.

I am thankful to those “original” musicians with whom I can get out of the mould of traditional guitar-making. Our collaborative experiments enrich the design of all the other models, albeit in minute details. Inquisitive minds think alike.

Guitars are often swapped by professionals. Amateurs pass them down to younger members of their family. Thus the son of a guitarist sometimes asks me to overhaul a guitar which my father built for his. Or for his grandfather! This is a delight for me, for, having been played a lot; the instrument is “mature” and answers your expectations. Unless something terrible has happened to it, it needs little attention before it can be played again.

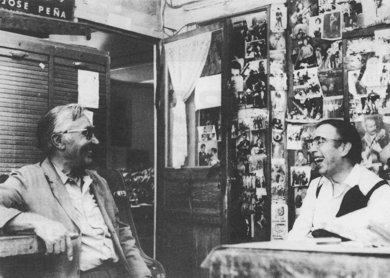

An interview of Jacques Favino

by Patrice Veillon

Paris june 11, 1994

How did you discover guitar-making ?

Out of the blue. But the moment I came across that trade, I fell in love with it. I was fascinated by the sounds you could draw out of a violin or a guitar. That was in 1945. My father arrived in France in 1922, and my mother and I in 1923, when I was three.

And what did you do before 1945 ?

I took the School Certificate, which I passed with distinction. My father was very strict about that sort of thing…

After that, I started an apprenticeship with a cabinet-maker. I loved working with wood. My boss would say to me: “Machines are not for you”. I did everything with hand tools, such as frame-saws, wood chisels or trying planes. The only power tool I sometimes used was the slotting machine. I would assemble small pieces of furniture. I was teaching myself to use the tools. Later this proved very useful for the guitar.

Then, one day, I found myself without work! So a friend got me a job in his firm. He was a foreman in a light engineering workshop. I soon learned to become a metal turner, a job which caused me to be sent to Germany in 1943. Marshal Pétain was sending us there to replace sick prisoners for six months. The experience lasted thirty months! I never forgave metal work for causing me to be sent there and I had nothing more to do with it.

So, on your return, you started in Busato’s workshop ?

Exactly. Through Gino Papiri, my brother-in-law, who was a friend of his. In those days, the workshop was making guitars, copied from the Selmer models. Busato offered me a position as foreman, but I refused, as I had no experience. I asked him to take me on as a normal worker. I wanted to understand the fabrication process. “Put me at the workbench first. If you are pleased with my work, let me be a foreman later.” I must admit I didn’t know the first thing about guitar-making !

Was Busato famous at that time ?

Certainly. He had 26 workers then, and more than 30 later on. The firm had diversified, also producing accordions and drum-kits. My job was to make the necks of banjos. I made them by hand, sculpting the head. Albert Uderzo’s father was a violin maker. I met him at Busato’s. I remember the son, who, as a child, helped out in the father’s workshop.

Then, I met Chauvet. He was a champion! He had been trained at Mirecourt. He saw what sort of a manual worker I was and one day he said: “I think you have it in you to make violins. If you want, I can teach you. It is more delicate than making guitars, but I think you can do it. I supply the shops in Rue de Rome”. Most violin makers contracted repairs out. There was an opportunity for me. I seized it.

After my day at Busato’s, at 6pm, I would go to Chauvet’s, Rue des Moines, until 11pm, often longer.

How did your apprenticeship go ?

The revelation didn’t occur at Busato’s but at Jean Chauvet’s.

When I stepped into his workshop, I found everything so beautiful, so delicate, violins as light as feathers. It was magic. I was fascinated by the fine construction, the sculpted soundboards; I admired the curves, everything was magnificent. I fell in love with it.

Six months later, I had finished my first violin. He was disgusted. He said: “It took me three years to make my first instrument”…

With Chauvet I formed a good team. So, in 1946, I left Busato and we moved to 9 rue de Clignancourt, in the 18th arrondissement, as partners. We shared the shop and the work. In due course, Jean took care of the violins and I produced double-basses and guitars.

What sort of guitars did you make ?

At first I would only do overhauls. Then, little by little, I acquired my own customers. With time, I found the guitar more interesting than the violin. It seemed easier to make, and I discovered that it offered a greater scope for discovery and research.

My first one was a jazz guitar with FF sound-holes, influenced by the Busato design, with a bulging back, but with my own ribbing. I started studying the whole problem of guitar-making. Why did we obtain this or that effect? I had to try out many ideas before finding solutions. I was beginning to understand how sound is transmitted. And so, little by little…

At that time, 1949, I think, L'équipe à l'atelierI met Matelo Ferré. I had been delivering guitars to Major Conn, a music retailer at Place Pigalle, and he was waiting for me outside. “Did you make these guitars yourself? Would you like to make me one?” He wanted a large classical guitar with steel strings. He was my first private customer. Matelo got me started in the business. I will never forget his initial help. We are great friends. Other musicians saw his guitar, and orders started arriving. It was suggested I should try and make guitars similar to the Selmer type. My first guitars didn’t play like Selmers. I nearly obtained their sound, but never completely. I gave up and carried on with classical guitars and jazz guitars with FF sound holes, since there was a demand for those.

I was working towards the Favino sound. It is a sound which other guitars don’t have. Sometimes I listen to a recording and recognise the sound of one of my guitars. I can’t play, but I have a good ear. I taught myself how to make guitars. If I had gone on making violins, I would have done research, but it was easier to progress making guitars.

You have to learn how to approach wood : stroking it to feel its grain.

How did you purchase your wood ?

I went to the Vosges or the Doubs to get French pine, maple or ash. I’d take my pick from the trunks lying on the ground. The warp must be less than 1cm per metre. For exotic wood, I used importers.

I had to see a guitarist play to assess his style of playing. I could, in this way, customize the instrument for him and improve my own technique. In a sense, the musicians taught me my job. They came and played, I listened and assessed them.

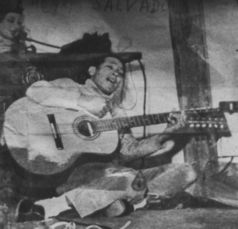

Then, in the early sixties I made folk guitars and the first twelve-string guitars made in France. It started with English instruments coming in for repairs. I even made a small twelve string for Joan Baez. Maxime Leforestier brought her to the shop. I didn’t like the square shape of the first folk guitars I saw. I made folk guitars, among others, for Maxime Leforestier and his sister, they called themselves “Cat et Maxime” in those days, as well as for Mannick et Jo Akepsimas. The shapes are often copied from others, and altered according to the maker’s taste. Even Jean-Pierre alters my models and I am happy to see him improving my designs.

Making folk guitars, I followed my instinct, altering the ribbing, without the counter brace which Martin used to put in. I repaired many a sound board when the back bracing had broken at the cross and the face collapsed. My research concentrated on the ribbing and on the thickness of the back bracing. What matters most is practice and the will to get things done.

Retailers made a mistake in going massively for Japanese instruments. They stopped giving us work, whereas we continued to send them customers. I started asking them for longer delivery times, and then I stopped serving them altogether. It was due to this Chauvet committed suicide: he had no work.

One day, Antoine Bonelli, Tino Rossi’s accompanist, brought me a Selmer for repairs. The sound-board was dead and had to be replaced altogether. “If it works, I’ll order two more”, he said. I therefore removed the top and discovered the famous Selmer ribbing. To get a more vibrant sound, I somewhat altered the ribbing for the new sound-board. To my mind, the sound was better than Selmer’s. It worked so well that Bonelli ordered “Favino Selmer-type” jazz guitars. He was our “agent” in Corsica ! Paolo Quilicci and others came later.

By the way, what do you think of the Selmer myth ?

Or should we say the Django Reinhardt myth? The sound also comes from the way you play; another musician wouldn’t have got the same sound from Django’s guitar. You’ve got to admit they were excellent guitars, except for the way the inside was finished off… Not very pretty… very rough. On the fingerboard, the original frets gave out a metallic sound: they were cut square and partly glued on to the finger board. But did you know I have manufactured Selmers?

I don't understand ?

Selmer ended their production in 1952. They still had orders on the book and, as they had a few necks in stock, they commissioned me to produce the rest. I must have made about ten. I remember a customer arriving one day and saying: “Look, Monsieur Favino, at last I have found an old Selmer”. I looked at it and said: “I made that one myself”. As he didn’t believe me, I told him the story and showed him two left-over Selmer necks with the name stamped on them. I learned a little while later that he had sold it.

So, there are Selmers which are in effect Favinos ?

Yes, the ones bearing the latest numbers. Purists are in for a shock.

Have you ever met Django Reinhardt ?

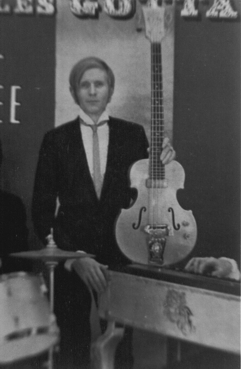

Never. I would overhaul his guitars for him, but they were brought to me by his brother Joseph. For Joseph, I made three classical guitars which he played in Russian night-clubs.Henry Salvador

What repairs did you carry out on Django’s guitars ?

Cracks, fingerboards that needed straightening out or fitting with new frets; the necks would warp as the differences in temperature and moisture were very problematic.

I didn’t have time to go and see the musicians on stage very much. In any case, they played for us in the workshop and I loved it. There were great moments when Matelo came, or Boubou and Elios, Louis Fays, and later Raphael, whom I have known since he was a baby, Birelli and others. They were very young and so gifted. I am glad they started out using my guitars. All my customers advertised my workshop for me.

My colleagues kept asking me: “How much do you pay them to spread the word about you?” and I would reply: “Nothing. I listen to them, and when they need something, I don’t let them down. That’s all.” I made myself useful to many of them. Their job was to play the guitar for money. I didn’t have to pay them. They were satisfied and they even sent customers to me. I have been very lucky. I was surprised to see how quickly I was becoming known.

My reputation was such that a lot of people were surprised to hear I was still alive…

They would come to my workshop and say: “Are you really Favino?” They were expecting a factory. My only advertising was word of mouth. My guitars were never exhibited except by Beuscher or Major Conn. Otherwise, no exhibitions, no direct advertising. The customers were my publicity. Sometimes a specialist magazine would publish an article about me .

You have been called « guitar-maker to show business ». Did you like this label ?

Many stopped coming to my shop. The word show business meant that I was terribly overpriced. It didn’t help. When I told them the price of a “Brassens” guitar, they would ask: “Is that really the price that Brassens pays? Brassens’s guitar doesn’t cost more than that?” They thought I was going to make them a cheap imitation. “Will it be the same as Brassens’s?” “The same. At the same price”.

Did Brassens always order the same model ?

Always. He always wanted the same sound, his sound. He left me free to choose the rosace, the edging and the other decorations. On the first one I made him, the one that followed him everywhere he went (he suffered terribly from stage fright and found it reassuring to play on his most familiar instrument), there were no frets on the fingerboard beyond the twelfth. He had invited me to his dressing room at Bobino. I asked him: “Monsieur Brassens, why don’t you bring me your guitar ? The bottom frets have all gone.” He said: “I never use that part of the finger board”. When the top frets were worn, he would replace them himself with frets taken from the bottom of the fingerboard. “Bring it to me”, I said. He replied: “I didn’t want to bother you”. I also noticed there were notches cut into the neck in several places. I said: “What have you done to the neck of your guitar?” He said: “Not a word about this to anyone. These are my own personal marks. I slide my thumb along the neck without looking at it, and when I feel a notch, I know I am in the right place for my chord. You mustn’t remove them, whatever you do!” That was in the beginning. After that he stopped tampering with his guitar. I was reserved. We were formal with each other, and yet we were friends.

How many of you worked in the shop ?

We were three. Then, from 1973, four, when Jean-Pierre joined us.

How many guitars a month did you make ?

Between 15 and 20. I always had about 50 in my order book. I would ship them across France. I also had European customers from Germany, Britain, Holland and Belgium. Some guitars were sent to America.

How was the workshop organised ?

Each of us could have done the work of the others, but the sound boards were my domain. I knew what to do to produce a particular sound, since it is essential to remember who you are working for. I have seen the evolution of my craft from the guitars returned to me for overhauls. I have never learned to play. My fingers won’t do it. “Why don’t you learn?” “I’ll never manage to produce the sounds I hear, and then, tools harden your hands”.

Did you encourage Jean-Pierre to carry on your trade ?

Not really, because of the Japanese. I didn’t know how long things would last. He studied Applied Arts and whenever he was free for a moment, he would come to the workshop. At College, they asked him how and where he had learned how to wield tools…

Was Jean-Pierre’s apprenticeship long ?

No, he loved the work immediately.

Was he critical ?

Yes. There were things he didn’t tolerate. He is creative. The three-rosace model is his. You would think today it is an old guitar.

Does a guitar get better with age ?

Yes, very much so. The more you play it, the better it sounds.

Which artist made the most lasting impression on you ?

For me, it was definitely Brassens, with his kindness. I met him when he was starting. His first guitar had been given him by Jacques Grello, a comedian, who sent him to me later. He said: “Can you make me one with a different sound to it?”. Later, he would poke fun at me about that. When the TV came to shoot in the workshop and a journalist asked him if he thought his guitars were good ones, he said: “He forced them on me”. He gave me excellent publicity by having photos taken in the workshop printed on his record sleeves.

How many guitars did you make for Brassens ?

About ten and Jean-Pierre three.

But what did he do with all those guitars ?

Some he gave away. He would leave some at his friends’ houses to have them close at hand. “When I have an idea, I pounce on my guitar!” he would say! ". Same thing with Enrico Macias. Both Jean-Pierre and I made him several guitars. We wonder what he does with them. He obviously doesn’t break them up, since Jean-Pierre has recently overhauled a few for him. That’s because he loves them. I am glad of that. Enrico has often mentioned me on the radio or TV. It doesn’t cost anything to be nice: I once helped him out of a problem by lending him a guitar; he has never forgotten it.

When and how did you stop working ?

In 1978, for health reasons. A cardiologist friend of mine, a former customer, told me: “If you want to live to a ripe old age, you have your son who does good work, so, you let him work and you give yourself a rest”. I had this trade in my bones. And now I wouldn’t have the strength to make a fingerboard !

Have you other passions ?

Fishing and listening to music.

Do you miss Paris ?

I don’t. But I do miss my work.